Monte dei Cocci

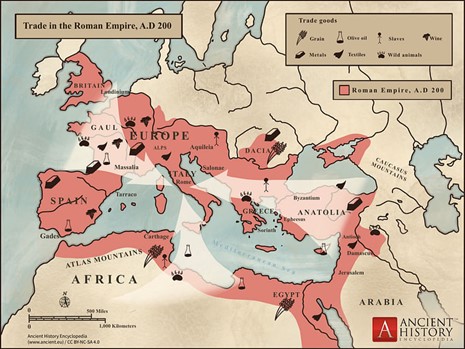

The area around Porta San Paolo in the southern part of Rome for centuries was a major commercial area. The port of Ostia, just 16 miles from the capital, traded with other Mediterranean countries, also from the Red Sea, Africa, Middle East and even India. The goods were transported by cart on Via Ostiense on a straight line from Ostia to Rome. In the area today called Testaccio, goods were sold wholesale or stored in warehouses to be sold around the city.

|

| The extensive Roman trade network |

On the banks of the Tiber there was also a river port where smaller ships could dock. Some ruins of the ancient warehouses can be seen from a bridge (Ponte Sublicio).

Trade involved foodstuffs (e.g., olives, fish, meat, cereals, salt, prepared foods such as fish sauce, olive oil, wine and beer), animal products (e.g., leather and hides), objects made from wood, glass, or metals, textiles, pottery, and materials for manufacturing and construction such as glass, marble, wood, wool, bricks, gold, silver, copper, and tin. Especially with east Africa and India, ivory, spices, silk, wild animals, and turtle shells. Finally, there was, of course, also the substantial trade in slaves.

Terra cotta amphorae

The containers used to transport wine and olive oil were made of terra cotta, called amphora, and could not be reused. (There was no plastic then…) So they were thrown in an area where they accumulated for centuries and became a hill, the Monte dei Cocci or the hill of shards. This artificial hill is still there in Testaccio and is 100 feet high and 1100 yards around. The name Testaccio comes from the word testae that is fragments of terra cotta amphorae used as containers for transport. It is estimated that 53 million amphorae were tossed here and that the hill reached a height of 300 feet, then slowly eroded.

|

| An aerial view of the Monte dei Cocci |

On this hill we have mainly amphorae from the state olive oil imports and, of course, for a city of a million people considerable additional quantities were imported privately. Only a small part of them was recycled as construction material: all the others were therefore smashed and their shards then neatly stacked in what, over the course of more than two centuries, became a huge pile raised not far from the docks. The order in which the materials are arranged, the presence of lime in the ground spread at regular intervals to mitigate the bad smell deriving from the decomposition of food residues and the existence of a well-designed inclined plane which allowed to reach the top on board of carts, suggest that the landfill was not improvised but carefully planned.

For centuries the Romans exploited the insulating properties of clay to carve out numerous caves on the slopes of this artificial hill, inside which the temperature is around 50 °F all year round. The rooms dug out in the shards were used as cellars, pantries or stables. Starting from the Middle Ages they housed taverns and, from the modern and contemporary age, restaurants and nightclubs.

Excavations carried out on the site in 1881 reconstructed the approximate age of the mountain and the origin of the pottery itself; in fact, thanks to the inscriptions found on some of them, it was possible to ascertain that most of the amphorae came from the coasts of Bizacena (in today's Tunisia) and from Betica (today's Andalusia); the oldest find was dated to the year 144 AD, the most recent to 251.

Each amphora, from the moment of its creation, bore a manufacturer's stamp and, once filled, the so-called tituli picti, i.e. information such as the content, the name of the exporter, the date of dispatch, the place of provenance and in some cases also the destination. The examination of the different types of amphorae in the various layers and the indications of origin and content, also constituted a precious source for reconstructing the history of trade in Rome.

To show how traditions can last, up until the 1950’s still some people in the area were throwing old terracotta pots on the hill. Now at the base of the hill, excavated in the ancient shards, we have many restaurants and night clubs and the entire neighborhood of Testaccio has changed from being a working-class area to a trendy one, where you can’t find a parking spot on Saturday night.